Thanksgiving 1895, Chicago.

How Chicago newspapers reported the holiday 130 years ago.

Friday, November 21, 2025. Good evening.

I almost just “re-stacked” last year’s substack about Thanksgiving in 1896 because it’s honestly pretty good. But I decided to write a new one about how Thanksgiving was observed - and reported - 130 years ago this year. When I looked more closely it turned out to be a pretty memorable week.

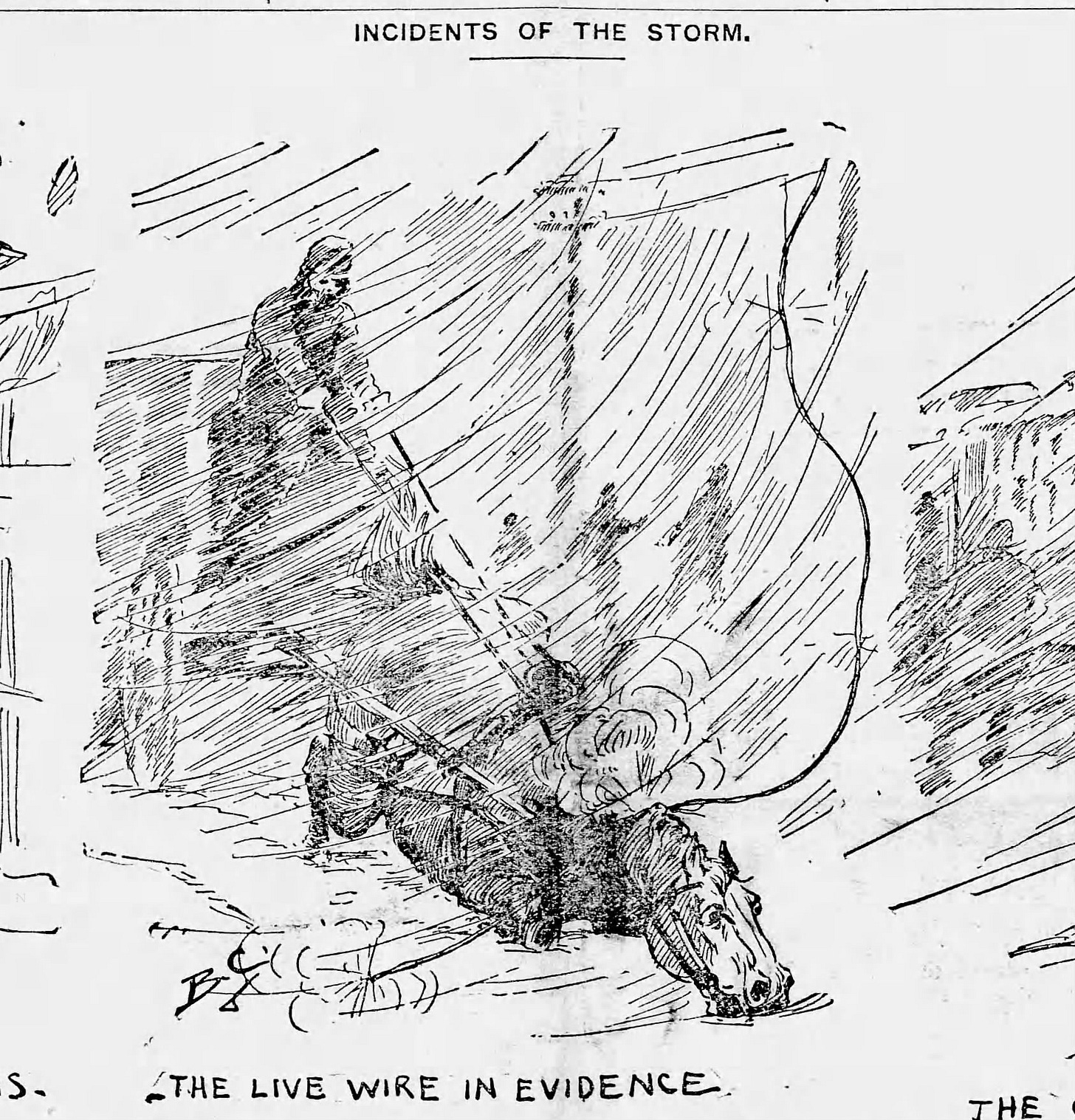

Firstly, that Monday, Chicago was hit with a terrible storm that knocked out telegraph and electrical wires and made travel on anything with wheels almost impossible. The lines of the trolleys came down, and the trolley cars, which so many had come to find indispensable, became mired in the snow and sleet. Several were electrocuted and died from the many live wires. Some froze to death. Boats on Lake Michigan were wrecked or men were stranded on their vessels for days while tugs struggled to handle the traffic.

By Thursday, the news of the storm had been relegated to the inner pages of the newspapers, and the talk on the front was all about Thanksgiving day.

Today, we celebrate Thanksgiving similarly, with football, feasts and donations to those less fortunate. I think Thanksgiving services are not as ubiquitous as they once were.

The newspapers covered the meals provided the poor, aged, sick, and incarcerated with a remarkable level of detail.

‘SICK BUT NOT UNHAPPY” was the headline on page 9 of the Chicago Tribune on Friday November 29.

In the County Hospital, it was reported that

“the brightest spot in the great pile of buildings which constitute the hospital was the children’s ward…One little tot with blonde curly hair was told she must not have the good things which delighted the others, but she begged to be taken from her cot and placed in a chair at the table in order to see the others eat and her wish was gratified. She apparently had as much fun as the rest…”

At Presbyterian Hospital:

…the regulation dinner was served to such patients as were in a condition to partake of such hearty fare, while ‘typhoids’ and other convalescing fever patients were limited to fruits and ice cream and similar frivolities…”

On the same page was a column about how Thanksgiving was honored “in asylums and jails.”

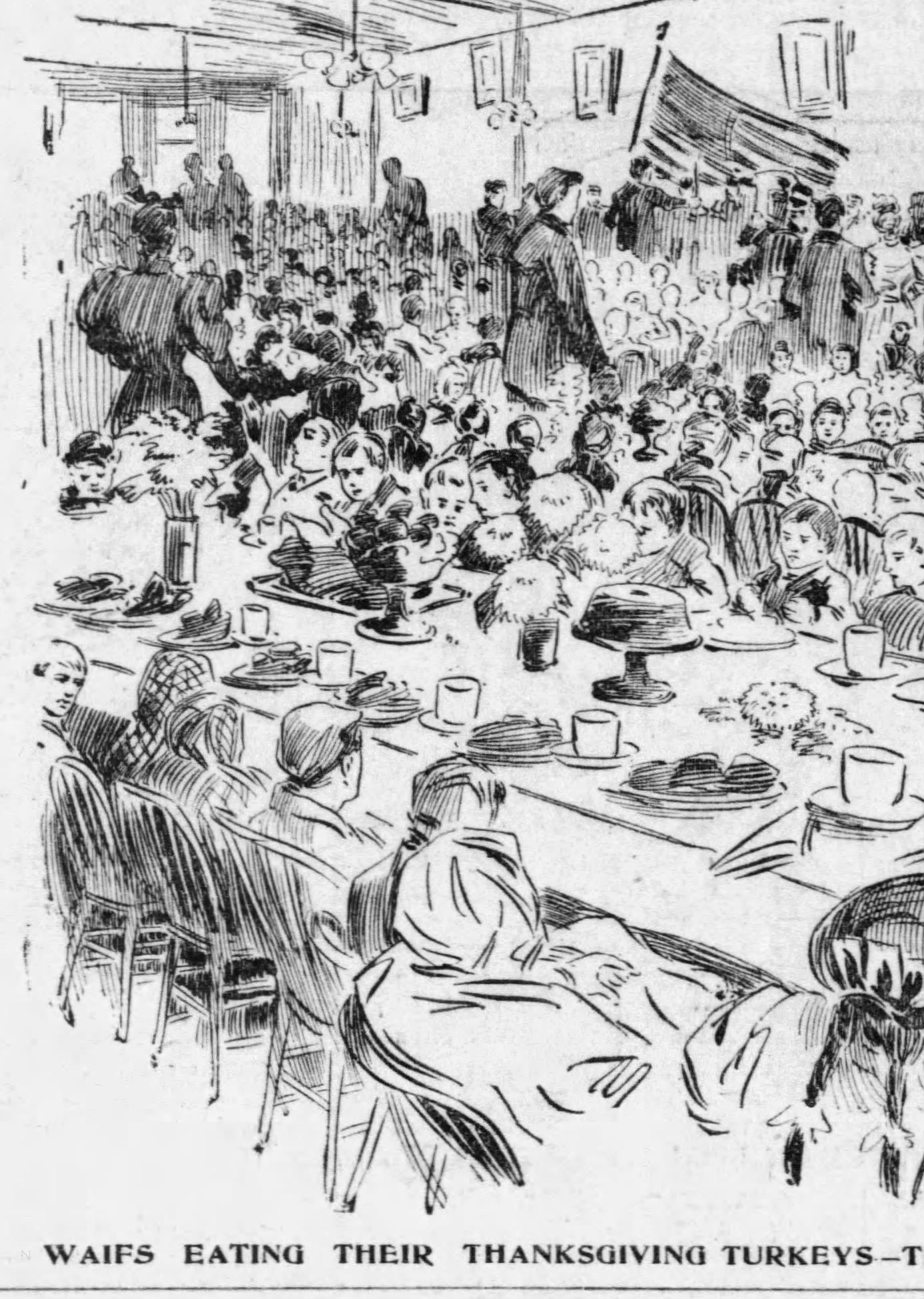

And so went the descriptions of festivities for 10 or so institutions - including the “Children’s Half Orphanage Asylum,” which was exactly what it sounds like, an institution for children who had one surviving parent unable to care for them. Because there was no government safety net, the institutions relied on the largesse of the wealthy to provide the meals. Mayor George B. Swift was reported to have provided six barrels of apples to the Waif’s Mission.

In 1895 the Waifs’ Mission decided to open its doors to “every waif and every neglected child in the city…white and black, girls and boys, good and bad, those who have no homes, and those who wojuld be happier if they didnot not have places which can be called home only by courtesy…”

Many of these waifs were newsboys, either homeless or helping to support their families. Likely the same boys who delivered the Thanksgiving newspaper were treated to a meal later that day.

The Chronicle reported on some who did not receive a meal that day. “NO DINNER FOR OLD PEOPLE,” ran one headline. The nuns at the Old People’s Home at Harrison and Throop announced that no donations

had been received, so no special meal would be served.

Another group of Chicagoans who went without a Thanksgiving dinner that year were the “cash girls,” the girls who rang up sales at large retail stores. The Chronicle reported that the ladies of the Alpha club would not be able to serve the girls that year because

The majority of the managers of the stores refused to allow the ladies to distribute the dinner among their employes on the ground that they were not objects of charity….This was much to the disappointment of the ladies of the organization and the 1,200 children for whose benefit it was planned. - Chicago Chronicle, Friday, November 28, 1895.

By the by, there were a number of institutions in 1895 Chicago whose titles at least have become obsolete with time.

• Home for the Friendless. This housed children, more or less temporarily, if a parent was in jail or some such. According to one article about this place, it housed “the foundlings, the waifs and strays…” Another article seemed to describe it almost like an animal rescue, where a little girl who was lost was dropped off at said Home, where she was united by police with her mother who had been looking for her.

• Foundlings’ Home. This seemed very similar to the above. In fact the Chicago Chronicle published a long story about a couple who had left their baby with the mother’s uncle to go out for the evening. The uncle, who had had plans of his own that night, dropped the baby off at the foundlings’ home, neglecting to pick it back up upon his return.

• Industrial School for Girls. This was a school for homeless, impoverished, or “vicious” girls, where they were taught skills that “the girls could become independent and productive members of their community.” There was a “Training School for Boys” which served a similar function. Honestly, these seem more humane than today’s juvenile detention facilities or “residential treatment facilities,” which serve at best as warehouses for troubled children.

• Asylum for the Poor and Insane. Although it was not called this, Dunning Asylum was an institution for those who were either destitute or mentally ill. I’ve been wanting to write a piece about this place. I don’t know how or whether the populations were ordinarily segregated, but on Thanksgiving the Tribune reported that after the poor were fed their turkey dinner, they then “settled into peace and quiet,” while the mentally ill were “given an evening of dancing and pleasure.”

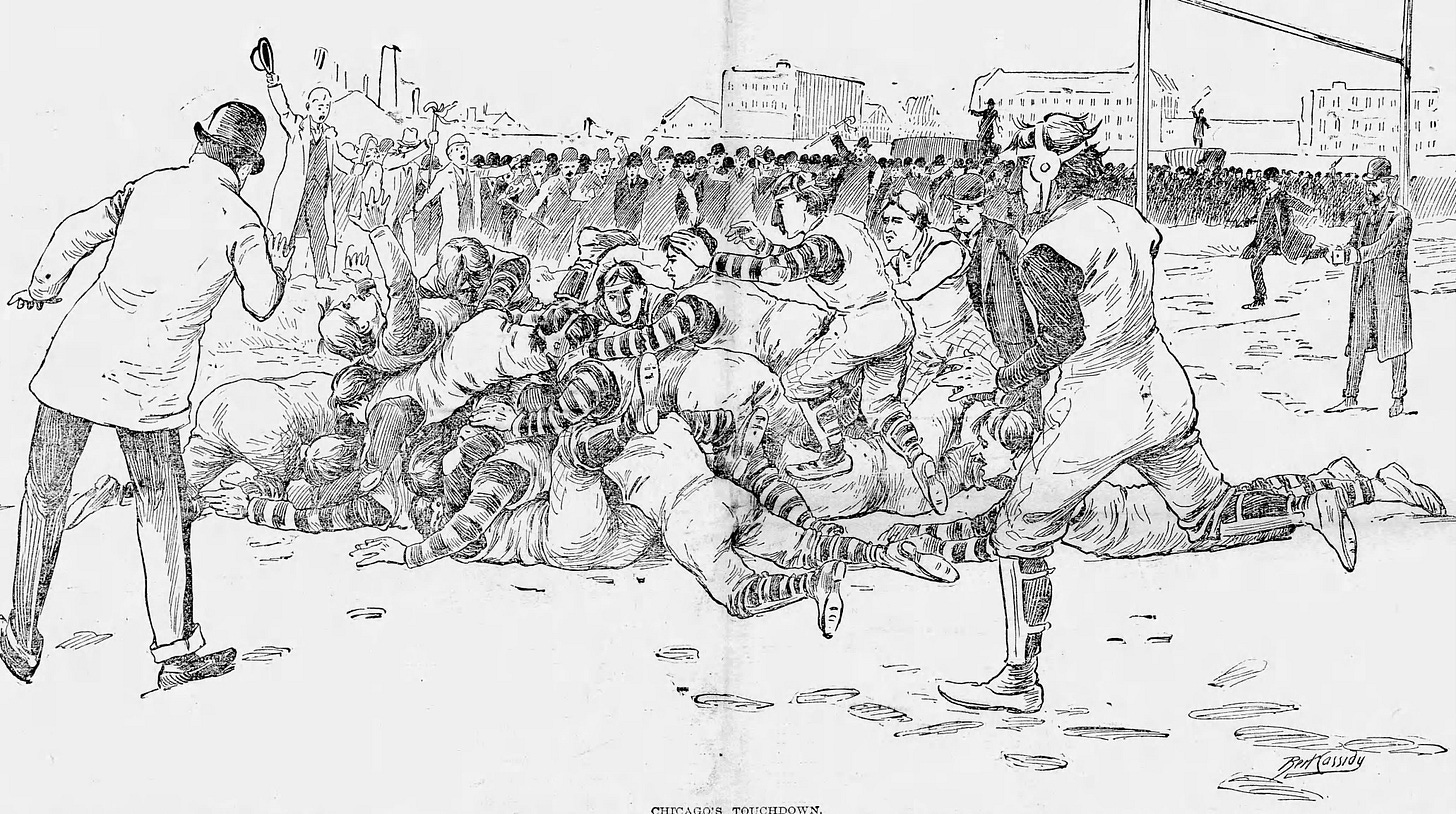

But enough about charity. What made page 1 on Thanksgiving was football. The Chicago Tribune had two articles on page one. The first one, above the fold on the right-hand side, concerned the game between the Boston and Chicago Athletic Clubs, which tied 4-4. (Evidently, back then, a touchdown counted for 4 points, and there was no overtime.)

The second one was about the University of Michigan’s defeat of the University of Chicago in the Thanksgiving Day game, two touchdowns to zero. “Chicago as a Good Second,” ran a subhead, which seems to be overstating the case.

The Chronicle’s entire front page was devoted to football. Along with the scoring system, the uniforms have changed as well.

It’s not until Page 5 that an article is printed about Thanksgiving meals, and that’s about a condemned prisoner is allowed to have a Thanksgiving meal with the rest of the prisoners along the “dead man’s corridor” of the Cook County Jail.

Yet another sporting event made news on Thanksgiving 1895, an event so unremarkable at the time that the Inter Ocean and other papers didn’t even cover it. It had been promoted and sponsored by H.H. Kohlsaat, the publisher of the Chicago Times-Herald.

The Duryea “motocycle,” also known as a motor wagon back then, had been invented and constructed by the Duryea brothers in a bicycle shop in Springfield, Massachusetts. It was the first successful gasoline-powered four-wheel vehicle ever constructed in the United States, and also the first to win a race of the newfangled machines. This was the second attempt at the race. The race had been scheduled for November 3rd, but of the three vehicles in the running, one failed to climb a hill without being pushed by humans, and another fell into a ditch.

On Thanksgiving Day, with the snows still lingering from Monday’s storm, six vehicles headed out from Jackson Park. After 10 hours and 17 minutes, the Duryea returned, beating out the Benz-Mueller on a 55-mile race to Waukegan and back. The Benz arrived at the finish line about an hour and a half later. The others took so long to arrive - if they ever did, some becoming lost or wrecked, one colliding with a streetcar - that by 2 a.m. when three stragglers arrived, “the judges had become disgusted and quit and no one witnessed the finish but two reporters.” Below is a photo of the Duryea in the snow that day.

By the end of the following year, the Duryea Brothers - Charles and Frank - had sold thirteen of the automobiles, making them the first mass producers of cars. And the first car salesmen. By 1905 they were manufacturing sixty cars a year. Three years later, Henry Ford’s Model Ts rolled out, and the rest of the Duryea story is consigned to the dustbins of history. Today of course, we celebrate yet another holiday - Memorial Day - with another auto race, the Indy 500.

Anyway, that was Thanksgiving week in 1895. It began with a storm that threatened to dampen all holiday activities and ended with a little-heralded hint of things to come.

May our upcoming holiday begin as mildly as the weather will allow, and may today’s signs of omen turn out to portend less than we fear. And most of all, may you enjoy the holiday, and do some little thing to ensure that others less fortunate may enjoy the holiday as well.

Thanks for reading!

Jen

Resources

Donate to the Prison Journalism Project.

The automobile race detail is fascinatin. A 55-mile race taking over ten hours in a snowstorm, with judges giving up by 2 AM because the stragglers took so long. Imagnie trying to explain to someone back then that in 130 years these machines would be everywhere and go 60+ miles per hour on highways. Sometimes its the footnotes that reveal the most about how radically things can chang.

I enjoy this column in general; and today, thoroughly enjoyed this well woven one, and its fantastic illustrations. Pathos, humor… thanks Jen.