Preface to the Book

Most of my posts will be short, but this one isn't. I wanted to let you know how I got started on this project.

PREFACE - updated February 15, 2023

“There is not a crime, there is not a dodge, there is not a trick, there is not a swindle, there is not a vice which does not live by secrecy.” ― Joseph Pulitzer, publisher

“He was probably a crooked contractor.” That was my dad on the rare occasions when the topic arose: How did his great-grandfather, George B. Swift, come to be mayor of Chicago in the 1890s? My grandmother would purse her lips with irritation at her son but venture no evidence against same.

It’s curious, thinking back, that this family of journalists, newspaper publishers, and political junkies seemed so incurious about how our forebear came to run Chicago. On the other hand, maybe the possibility that he had gotten the job through patronage was no more distasteful than the idea that he might have had to run for office.

What my grandmother did tell us about her grandfather: He never drank alcohol and didn’t even serve it to guests (which seemed indirect evidence against being either a crooked contractor or a Chicago politician). George had been mayor for a term or two in the 1890s. According to family lore, Swift had insisted that Grant Park be named not after himself but after family friend Ulysses S. Grant (a claim for which I can find no evidence). The only visible trace of my great-great-grandfather at my grandmother’s home was a stunning ceremonial chair of marble and mahogany, a gift from the Mayor of Chinatown in New York City, that stood in the shadowy foyer. Another relic was a beautiful copy of a campaign portrait from 1895 from Cousin Cliff, who I later learned had long ago been intrigued by this story.

Years later, Erik Larson’s riveting book about murder and mayhem during Chicago’s World’s Fair in 1893 revived my interest. I knew by then that Swift had been mayor in 1893 and 1895. Readers of “Devil in the White City” will remember that Mayor Carter Harrison had been assassinated at the end of Chicago’s World’s Fair by a disturbed newspaper carrier named Eugene Prendergast. The book ended there, but the aftermath of Mayor Harrison’s assassination hadn’t. In the tumultuous days that followed, George B. Swift had somehow become Chicago’s next mayor.

Why Swift? What events led to his selection? I was curious but had no time to follow up. My children’s father had died suddenly, and for years I was consumed with caring for the kids and finding work that didn’t interfere too much with home.

I moved from writing to politics to government work in the intervening years. Getting hired for President Obama’s first campaign opened the door to other campaign work, and by the fall of 2016, I had decided to leave my job as a manager in the Communications Department for the Connecticut House Democrats. Donald Trump had been elected president and I knew I wanted to get back to political organizing.

Besides that, I had no fixed thought about what might come next. When I was invited to watch President Obama give his final speech in Chicago in January 2017, George B. instantly came to mind. I decided to dig further into who Swift was and how he’d become mayor.

The day after the speech, with President Obama’s themes of civic responsibility still swirling in my head, I took a bus to the Chicago History Museum. When I asked the librarian at the Research Department for information on George Bell Swift, she told me that, alas, mayoral papers weren’t retained as a matter of course in the 19th century. She did recall that Swift had overseen the implementation of Chicago’s civil service reform law, the first in the nation. She gave me a look. “At least he tried.” He also had been known for his efforts to expand the parks system. (Was there some truth to the family rumor about Grant Park?)

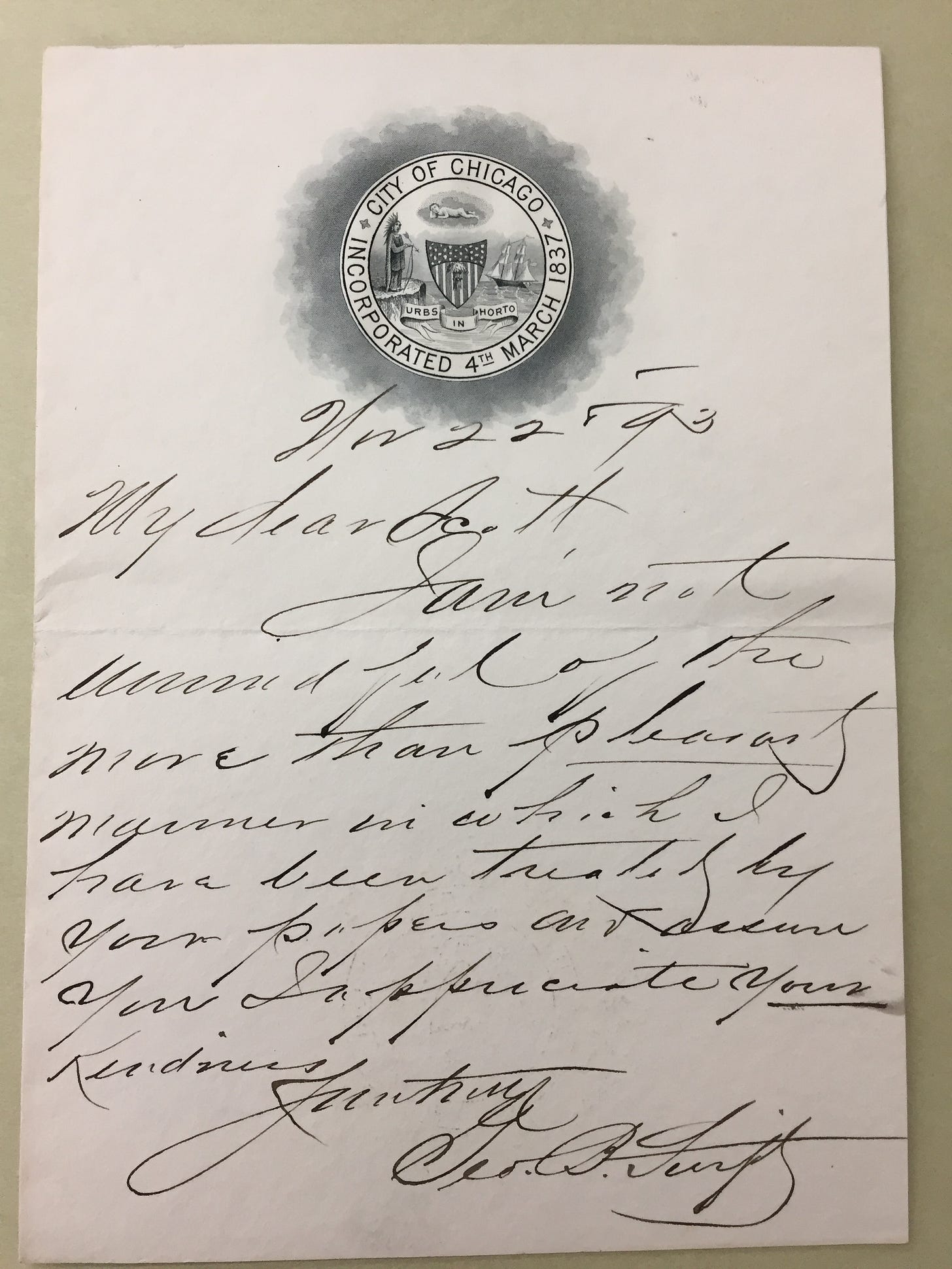

The librarian soon brought me a thin manila folder with his name on the tab. In it, there was one piece of paper. It was a letter from George B., written on City of Chicago letterhead, to James W. Scott. The librarian told me that James Scott had been the editor of the Chicago Herald.

November 22, ’93

My dear Scott,

I am not unmindful of the more than pleasant manner in which I have been treated by your paper and assure you I appreciate your kindness.

(Illegible),

Geo. B. Swift

I would later learn that George and “Jimmy” Scott had grown up together in Galena, Illinois, and often teamed up to fight a gang of kids down by the Galena River. [1]

I decided to read the Herald articles leading up to that date. It soon became clear why George B. had underlined those words to his childhood friend.

On the front page of the November 5 edition of the (Democratic) Herald, a quarter-page-sized cartoon captioned, “The Spectre Behind the Throne” showed (Republican) George B. appearing to usurp the crepe-draped chair of the assassinated mayor (Democrat) Carter Harrison. Yet another cartoon showed men in a melee in the room of the City Council. The headline read “Fight for the Place: Swift Claims Election by a Doubtful Majority.” On the front page of the November 7th edition, another large cartoon depicted George B’s mustachioed, bald head affixed to a lockbox.

This was not my grandmother’s George B.

It’s worth noting that had I started my search with a republican newspaper, I might never have pursued this story. The Chicago Tribune’s front page headline on November 7th read, “Swift is the Mayor - Easily Elected.” There were no cartoons.

But I had started with the Herald. I stayed at the Museum until closing time. I called my dad from the taxi back to the hotel and told him what I’d found. I texted a screen of his great-grandfather’s cartoon head on a cartoon lockbox. He was delighted; he knew nothing of any controversy over his tenure.

There was a story here; it just needed to be dug out.

At the time, newspapers across the country eagerly covered the story, but few books have described this transition of power. (Even a book called “Chicago's Greatest Year, 1893: The White City and the Birth of a Modern Metropolis” failed to even mention it.) Moreover, as I learned, fisticuffs were not uncommon at City Hall; it wasn’t even the first time that George B. had been involved in a physical altercation in that chamber[2].

In retrospect, this is understandable: The political crisis that followed the assassination of Carter Harrison lasted only a few days. In the meantime, lurid details of the mayor’s murder and the demeanor of the assassin were the lead stories of the day, and American news publishers were more broadly interested in the effects of the Panic of ’93, a stock market crash earlier that year that had led to a nationwide depression, and the widening gap between the rich and poor, which was providing impetus to the labor and progressive movements.

At the time, though, the drama of Chicago’s interregnum made the front page of newspapers across the country. Chicago was still on edge over the pardons Governor John P. Altgeld had given in late June to the remaining accused Haymarket bombers; four had been hanged almost five years prior[3]. Given the forces at play and the people on the field, Chicago’s fate was swinging in any of several directions. That a democratic process would choose the mayor was only one possible outcome. “Shame, Chicago, Shame” (Chattanooga Daily Times) and “Chicago on a Volcano” (Delaware Morning News) were two headlines that ran in newspapers in the coming days. The Chicago Recordworried about the consequences if the Chicago City Council was allowed to choose one of its own. Bribe-fed aldermen had pushed through several franchises for their private benefactors, only to have the bills stayed by Mayor Harrison’s veto. If a mayor were chosen from among them, the ordinances and the private utilities would have a free ride. There was also this concern: “…there is no telling when such a mayor so chosen would vacate his office.”[4]

Coverage differed drastically depending on the political orientation of the newspaper or even which candidate it backed. Sometimes a newspaper would omit facts - or whole stories - that were inconvenient to its candidate. One paper might term a political gathering a “caucus” while another might term it “incarceration” (and print a cartoon with a head on a lockbox). Thus one needed to read all the newspapers to understand a story. (If you wanted to know what the Dems were doing behind closed doors, you read the Republican papers, including the cryptic squibs on the editorial pages.)

It didn’t take long for me to see the parallels between this 19th-century political crisis and the crisis unfolding in our country under Donald Trump. Fox News became his mouthpiece, while MSNBC tried to do the same for democrats. Trump ordered his staff to repeat lies about the size of his crowds and the number of votes by which he’d beaten Hillary Clinton. The Left, for its part, was consumed by evidence that Russia might have put its thumb on the scale of the vote for Trump. Social media amplified misinformation and ginned up the increasing animosity between the parties. The more I read, the more I realized that I wasn’t just uncovering a piece of family history; I was uncovering an episode from American history that resonated like a bell at this moment in our country.

Unearthing the story has taken years of reading thousands of articles from the Inter Ocean, Chicago Tribune, the Evening Post, the Evening Journal, the Daily News (and its evening paper, the Record), Chicago Times, Chicago Herald (which later became the Times-Herald), the Eagle, the Chronicle, the Broad-Ax, and papers from around the country. I read dozens of books about Chicago, about the history of the press, about the men (and a few women) who shaped Chicago.

And what personalities these were in late 19th century Chicago; people (mostly, yes, white men) whose lives and purpose had been shaped by the Civil War, by the Great Fire in 1871, and by a growing divide of wealth and opportunity that, wave after wave, led to destitution, illness, and violence. The Haymarket bombing in 1886, the Pullman strike in 1894, Jane Addams, Ida B. Wells, and Eugene Debs are written into the history books, but less so the Beer Lager Riot of 1855, a cholera outbreak in 1885 that killed one Chicagoan in ten; and the Panic of ’93, a nationwide financial crisis that drove the poor to seek shelter in police stations and City Hall. That same year, Chicago’s Gilded Age patrons and politicians came out in their finery to dedicate both the Art Institute and Field Museum while also holding banquets for “waifs and newsboys.”

About George B. Swift? I learned that his rise to the mayoralty had not been a fluke. That his rise to power had begun in the 1870s when he formed part of the first Republican political machine[5] in Chicago. I learned who his friends and foes were and how quickly one could become the other. We know from the reporters’ epithets (“the Little Deacon,” “George Brains Swift”) that he was bright, unusually short of stature, and religious. A politician in a city swimming in saloons, he didn’t drink. He was outspoken, pugnacious, and irritable. But he was also practical and not ego-driven. (The librarian also remembered that he gave the shortest inaugural speech in history.[6] ) Judging by numerous interviews in newspapers of every political persuasion, he was also good copy.

I also learned how engaged newspapers and citizens were in city affairs. I read coverage of city council meetings that, improbable as it sounds today, were as entertaining to read as the Sports page. In an era before concerts and major sports venues, political and even government events were significant entertainment for the public[7]. Indeed, we only know the details of the critical events in this story because the newspapers covered governance as avidly as they covered politics. Aldermen knew it, and they played to the crowds - sometimes literally.

So many of the concerns of 19th-century Chicago will sound familiar.[8] Public health outbreaks hit the front pages back then, too: Vaccination clinics were routinely announced in the newspapers. Instead of government assistance, men such as Michael Cassius McDonald, “King Mike,” the infamous gambling impresario, doled out free lunches in exchange for the many hands he would need come Election Day.

Cities and their governments were also suffering growing pains. In 1880, an alderman opined during a council meeting that they had to stop allowing railroad companies to lay track down wherever they wanted.[9] Yet ten years later, few regulations had been created, and thus dozens of rail companies had laid down competing tracks through Chicago. Because there were no regulations for building tracks, railroad owners constructed them the cheapest way they could, laying them down on grade. Pedestrians were routinely run over and killed at grade crossings.

This will sound familiar if we substitute Meta, Twitter, and TikTok for Chicago Western Railroad, Illinois Central Railroad, and Charles Yerkes’ transportation empire. Lawmakers today have yet to understand social media well enough to create the kinds of regulations that would curb some of the most thorny problems regarding disseminating lies and conspiracy theories. The consequences could be as deadly to our democracy as grade crossings were to 19th-century pedestrians.

I had decided to research George B. to find out his story, but I decided to write the book to find out how our story turns out, or at least where it’s headed. Are we genuinely headed for totalitarianism or possibly a new progressive era? How can we tell?

No episode from American history occurs in a vacuum. This struck me the most clearly a few years ago when I was listening to Lillian Cunningham’s excellent podcast “Presidential. ” During her episode about Abraham Lincoln, she pointed out that Lincoln had been a young Congressman in 1848 when ex-President (and then-Congressman) John Quincy Adams collapsed on the floor of the House chamber and later died. Cunningham noted that many of Adams’ ideas about America’s potential for leadership in the world only bore fruit decades later, in part carried on by President Lincoln, who had first heard these ideas in the well of the House so many years before. Many people are involved in handling the baton, but the person who started the race will not be the one to cross the finish line.

Thus, I’m left to wonder if any threads of this story from 19th-century Chicago point the way for our country 125 years later.

One suggestion comes to us from the past, from another letter written in November 1893. It was published in the Inter Ocean on November 9, the day after the key events in this story took place. A minister - a Methodist, like George B. - felt obliged to write the new Mayor:

Dear Sir: Please allow me to congratulate you upon your election to the office of mayor of this great city. I am especially pleased because of the final action of the Common Council. It shows that in the midst of political corruption there is a controlling element of right and justice which prevails in times of peril.

As a citizen of Chicago I rejoice that in this case, when lawlessness was about to control, when right and justice were about to be trampled under foot, the better element of the Council prevailed, and in the name of honesty and integrity you were triumphantly elected.

I sincerely trust that these important principles will prevail during your administration. It is time that the pools of corruption should be purged and those elements which menace this great city’s continued success should be removed. All good citizens will rally to hold up your hands in the struggle for the enforcement of righteous laws. Very respectfully,

JAMES B. HOBBS.

Of course, not all the levers employed to get George B. elected were “done in the name of honor and integrity,” but we only know about this because of the diligent coverage by the newspapers. We only know about this letter because it was printed in a newspaper.

The story that follows draws themes from a close reading of history and attention to current events. But the story itself comes from that “first draft of history,” the newspapers. I am so grateful for the vivid writing and avid attention of reporters from over 125 years ago, most nameless, who gave flesh to the bones of these ancestors. They have helped me revive a story that will sound almost as if it could have been written yesterday, with insights that could hold lessons for tomorrow.

[1] 11/28/1893 Daily News

[2] On March 12, 1880, Swift, then an alderman, got into a heated argument with Alderman Frank Stauber, a Socialist, after Swift questioned the legitimacy of Stauber’s party. Swift evidently rushed toward Stauber “in the midst of considerable excitement.” It was up to then-Mayor Carter Harrison to restrain the two. (Chicago Tribune and Inter Ocean, 3/13/1880 editions.)

[3] The Tribune hated Altgeld so much that they called him “John Pardon Altgeld.” It didn’t matter that it turned out that the accused turned out to be innocent. It was William Penn Nixon, long-time editor of the Inter Ocean who called the disgraceful Haymarket Affair “the result of too much newspaper.”

[4] Chicago Record, October 31, 1893

[5] Swift became the youngest alderman in Chicago’s history in 1879 when he was elected at age 34. He and his friend and business partner Colonel George R. Davis formed the first Republican political machine in Chicago. During his time as Commissioner of Public Works in the 1880s, he was the first public official to stand up to the corrupt transportation tycoon Charles Yerkes.

[6] “Gentlemen of the Council: It has been customary for years for the Mayor-elect to indulge in an inaugural address. I think it unnecessary. The retiring Mayor has outlined the past in his message, I take it. It is for us to be of the present and the future. It is my hope and it is my belief that the executive, legislative and administrative branches of the city government will work in harmony, and it should be our desire, as I believe it is, to so fill our positions as will be for the best interests of all the people. What is the further pleasure of the Council?”

—Chicago Tribune, April 9, 1895, page 1.

[7] Age of Acrimony page 38

Aside from county fairs, political rallies were one of the few times that people gathered in large numbers for fun. Small wonder that county fairs are still populated by politicians during election season even today.

[8] A small matter, but one that will resonate today, was the “hat ordinance” introduced in the City Council in 1897: Theater patrons had asked Chicago aldermen to pass a law forbidding women from wearing hats more than a few inches tall at the theater so that people behind them could view the stage. Theatre owners protested that they weren’t about to enforce this law lest they lose their paying patrons. The ordinance failed.

[9] May 4, 1880 Chicago Tribune. Later that year, another alderman stated that if they were going to charge one railroad company for laying tracks down in Chicago, all railroad companies ought to be required to do same. That alderman was George B. Swift.